The Seawanhaka Steamship Disaster

Enlarged images found here

by Sophia Lian

The steamship era on Long Island had its boom in the 19th century, particularly along a major route on the Long Island Sound. With this new form of transportation, commuters could now travel from Manhattan to Long Island’s North Shore expeditiously in a time before the roaring transport of highways and the LIRR. Many visitors from New York City and working-class day-trippers from Long Island took advantage of the convenience the innovation brought. However, without the safety precautions we know today,

steamboat accidents were not a rare occurrence. The waterways neighboring New York City were packed with cargo steamships and passenger steamships. A cramped channel barely enforced safety regulations, and inadequate ship designs and conditions were enough to result in many incidents, in this instance, the Seawanhaka Steamboat Disaster on June 28, 1880.

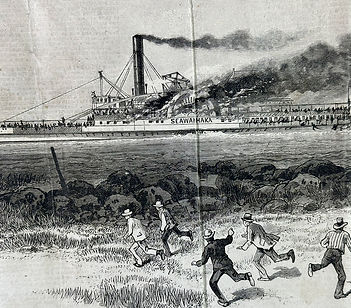

The Seawanhaka, built in 1866, was one of the Long Island North Shore Freight & Transportation Company's best-known steamboats for its speed. A trip to New York City from our area on the Seawanhaka took about three hours, a breakthrough for its time. The Seawanhaka steamboat served commuters traveling between Roslyn and Peck Slip (near today’s South Street Seaport). On June 28, 1880, the service of this steamship came to an end. In the afternoon, the steamship Seawanhaka was making its regular daily trip towards Long Island, filled with commuters after leaving the last Manhattan boarding dock. It was not long after 4:30 p.m. that the boilers of the steamship caught on fire between Hell Gate and Little Gate, and the flames spread rapidly through the decks of the ship.

Captain Charles P. Smith struggled to find a safe place to land the burning ship, with no docks nearby and heavy boat traffic on all sides. In the face of a life-or-death situation with the lives of passengers on the boat, Captain Smith attempted to land the steamship on a grassy point at the northern end of Ward’s Island. The strength of the tide pushed the ship back before it could advance forward onto the grassy end. In reporting the incident, a Dr. Howard described Captain Smith’s heroism as the Captain then set out to redirect the boat towards what seemed like the best option: the sunken meadow. Captain Smith used his force, bending down to the floor to keep the wheel in place and keep the ship on track. The flames that surrounded him didn’t stop him from performing his task until the ship was pulled onto the marsh. As a result of his bravery, his face and hands were burned as he remained at his post throughout the whole incident and was the last one to escape the ship.

The ship was found half on marshland and half in water facing the East River. Over the course of days, over forty people were found dead, and many were injured. The search for bodies continued in the days that followed the incident and the lists of victims grew longer. Many drowned in attempting to escape from the fire, and many were burned to death trapped in the vessel. The precise count of the deceased was never known.

Reports of the victims of the disaster told the public about the tragedies of the accident. A 10-year-old boy was found near the waters of the sunken meadow at College Point by employees of a rubber factory, his hair and face burned. Some that were found were not able to afford a burial. This steamboat accident was a catastrophe that resulted in the injuries and deaths of children, women, business owners, and prominent citizens.

With the increasing trend of steamboat accidents, the Seawanhaka Steamboat disaster brought public and government attention to the dire need for regulations within the industry. In the time that followed, visitors came to see the remains of the steamship, and small ships continued to look for the bodies of victims. One prominent passenger on the Seawanhaka when the catastrophe occurred was the former mayor of New York, W. R. Grace. As a first-hand witness to the consequences of insufficient regulations in New York’s shipping industry, Grace ensured that formal investigations were made and that reforms in regulations were being enforced. The cost of the disaster and those who died were not fully in vain. Light was shined on matters that long needed to be addressed in the safety of steamboat transportation.

Enlarged illustrations can be viewed here!

Sources include:

“The Burned Seawanhaka; Seeking the Causes of the Fire and Loss of Life. Sad Scenes at the Morgue. Describing the Disaster. The Lost Boat Not Racing. the Victims and Sufferers. How the Law Reads.” The New York Times, June 30, 1880.

“The Seawanhaka Saga Continues.” Great Neck Local History blogspot.com, 2011/05.

“Pilot,” Volume 27, Number 43 - 3 July 1880 - Boston College Newspapers.

“The Seawanhaka Disaster. - the Mercury - 25 Sep 1880.” Trove.

“The Seawanhaka Victims: Sixty-One Persons Either Dead or Missing...”, New York Times, July 1, 1880.